Received April 6, 2018, posted with permission. -jsq

When I called the Canoe Outpost on the Suwannee River in Florida to ask if they would give me a shuttle up to the Little River at Reed Bingham State Park, in Georgia, the woman on the other end said, “You want to start up there?” I told her my plan was to canoe the Little River from where it left Reed Bingham down to its confluence with the Withlacoochee, then follow the Withlacoochee to the Suwannee. “I’ve worked here 27 years,” she exclaimed, “and this might be the first!”

Photo: Kathy Hubbard of Burt Kornegay arriving at Troupville Boat Ramp, March 24, 2018.It turns out that, although many paddlers ply the Withlacoochee and the Suwannee with their blades, the adjective “little” in the name Little River means, in part, little paddled.

I’d had this trip in mind for years, and one reason lies in that word “Little.” When I see it next to a winding blue line on a map—and almost every state has at least one stream with that name—I immediately feel drawn to explore. I like the intimacy of small rivers, with banks near by and comforting, with trees so confiding at times I have to lower my head. I like the way little rivers reveal themselves bit by bit, bringing me close to plants and animals, bringing plants and animals close to me. I also like the way small rivers, often shallow, obstructed, keep out jet skis and powerboats—the scourge of quiet canoeing.

As for the Withlacoochee, which the Little flows into, the name is a combination of the Creek Indian words for “water” (with or we) and “little” (chee), so it too means “Little River.” I’d be paddling from the Little to the Chee. I packed to spend four days on each river, traveling around 120 miles total.

The etymology of Withlacoochee depends on which sources you go by. Here’s another:

“The Withlacoochee River received its name from the Muskogean peoples who inhabited South Georgia. It comes from the compound Creek word ue-rakkuce [IPA: wiɬakːut͡ʃi], from ue “water”, rakko “big”, and -uce “small”, with the rough translation “little river.”[2][3] English speakers then changed the Muskogee voiceless lateral spelled r to “thl”.”

2 Simpson, J. Clarence (1956). Mark F. Boyd, ed. Florida Place-Names of Indian Derivation. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Geological Survey.

3 Martin, Jack B.; Mauldin, Margaret McKane (2004-12-01). A Dictionary of Creek/Muskogee. U of Nebraska Press. p. 183. ISBN 0803283024.

So by those references it’s “oochee” that means little (not just “chee”).

Back to Burt’s story:

The Little River turned out to be well named. At the SR 37 bridge, where I launched, just downstream from Reed Bingham, its channel was only 3 to 4 canoe-lengths wide—necking down to not much more than a canoe-width in places. But, though small, the Little turned out to be big with beauty. It was bordered by loblolly pines and live oaks, with water elm, river birches and willows on the banks, and with large cypress and Ogeechee tupelos growing in the channel itself. The trees were hung with Spanish moss, and some of the oaks supported gardens of resurrection ferns on their big branches. Under the trees, swamp azalea was in full bloom, its blossoms ranging from white to pink. Occasionally I’d glimpse a farm field in the distance, but the farther I went downstream, the more stately the forest became, protected in a widening swamp.

Native wild azaleas, Rhododendron canescens.The Little was big on wildlife too. I started up deer, saw green, little blue, and great blue herons, heard barred owls and pileated woodpeckers, watched a swallow-tailed kite flying to its nest site with a streamer of Spanish moss in its talons. Twice I came on wild hogs, their hair as black and coarse as a bear’s. Because of the damage they do in rooting up the land, the hogs were animals I was sorry to see.

The Little was also blessedly quiet. There were no commercial flight paths overhead. It was paralleled by no interstate or railroad. I could hear the wind in the trees, and I could hear myself think. In 4 days I saw only 2 houses, both situated back on bluffs. The other occasional structures I came to were mostly fishing platforms on stilts with tin roofs and screens for walls. As for river people—fellow paddlers, fishermen, or anyone at all—I saw none, even though the weather was spring glorious.

The Little was a slow-then-go kind of river. It straightened and moved lazily along for a mile or so, then abruptly narrowed and sped up, twisted and turned. The more convoluted the river became, the faster it went. Several times I came to sections where the river entered a long, natural slalom course as it raced through groves of cypress and Ogeechee tupelos. The slalom gates were formed by tree trunks up to 8′ thick, and there were multiple routes to run. (See Martha Moore’s painting below of an Ogeechee tupelo, based on my last trip report about the St. Marys River.).

The level for my trip, which was 400 cfs starting out on the USGS Adel gauge, at Reed Bingham State Park, could not have been better for the fast-water swamps. The Little was high enough to paddle without grounding out in shallows, but low enough to expose small sandbars for camping. I never had to get out of the boat to pull over downed trees or to portage, but could always find a way around, through, or under whatever lay in my path.

The level on the Adel Gauge was around five feet (170.1′ NAVD88) and rising while Burt was on the Little River, which is a very good level: high enough to float over most deadfalls; not high enough to be flooding.

Back to his story:

Although I had the Little to myself, on the third afternoon I did come to a place where a man’s presence was strong. It was in the middle of what I named “Twenty Mile Swamp,” which lies between Morven Rd. crossing and Troupeville Landing, that I saw an adult-sized tree house nestled 20′ up in the limbs of a live oak, and there was a long swinging bridge leading up to the house. I landed, saw no one, and walked up the bridge. The tree house was open-sided, and everywhere lay the tools used to construct it—pulleys, winches, saws, block and tackle, ropes, hand drills, axe, bolts, steel cable, hammer. In fact, the place was still under construction. It was surrounded by deep forest too, so all the building materials either had been obtained from the woods or hauled there by boat. Some of the timbers were as big as telephone poles. Where was the builder? Who was the builder?

Heading on downriver and doubling the bend, I discovered that the tree house was just the suburbs. There were two more tree-lodged structures, one on either bank, connected by a long swinging bridge high over the river. Of course, I had to explore. Landing on a sandbar on the right, where there was a cast iron kettle and a tripod used to suspend it over a fire. I climbed a ladder up to the swinging bridge and gazed across the frail-looking contraption to the opposite shore. If this thing breaks, I thought, as I stepped out, I’ll have to swim for it.

The shelter that was almost hidden in the trees on the opposite side turned out to be a cookhouse, one in which many a meal had been prepared. It had a propane stove, pots and frying pans hanging from the rafters, open shelves holding cans of beans and tomatoes, as well as glass jars of home-canned meat of some kind. There were animal traps hanging from pegs, two deer hides draped over a rail, a sign quoting Thoreau about fishing, and no fewer than 19 fishing rods stuck here and there. There also was a floating dock with a walkway down to it. Most exciting, from the dock, I saw under the cookhouse, suspended from ropes, a 10′-long dugout canoe. It had been carved in the southeastern Indian fashion from a single tree trunk, with a shapely bow and stern.

Re-crossing the bridge, and still not seeing anyone, I walked to another structure: a small cabin up on poles. The cabin was sided with board and batten, had windows, and was wrapped on two sides by a porch. Climbing the steps to the padlocked door, I found myself facing a sign with the drawing on it of a revolver pointing straight at me; and beside it—should I have the idea of forcing the lock—was this warning: “Prayer is the best way to meet the Lord. Trespassing is faster.” The bullets showing in the cylinder, I noted, were hollow point.

And yet the place did not have a threatening feel. Another sign on the door said, “Gone Hunting.” This was someone’s home. A stack of freshly split firewood was on the porch. There was a wash tub, a hand carved canoe paddle, and many other items and furniture made from the swamp. The place was one of a kind, and it expressed the independent character of its maker.

Socially tucked behind the sign was a small printed card, and on it the picture of a man around my age, dressed like a frontiersman, with the name “Colbert,” and the motto, “Life free or die.” I wrote a note on the back telling Mr. Colbert that, passing through on a canoe trip, I’d stopped to admire his place. And I left my name and home phone number.

Besides Colbert’s arboreal multiplex, one other isolated human construction was equally surprising and pleasing to come on: an abandoned concrete bridge composed of large, handsome spandrel arches standing by itself in the middle of the swamp. It wasn’t shown on my topo map, and the bridge had been long-abandoned. The crowns of birches and cypresses, gums and oaks completely canopied the structure. Their trunks leaned and chafed against its railing. Climbing up the abutment, I discovered that the bridge deck itself had collected so much leaf matter over the years that trees were growing on it, including a couple of loblolly pines with trunks a foot thick.

Stone Bridge over Little River, SW of Adel, GAThe bridge was only 3 paddle lengths and 1 paddle blade wide, or around 17′. It had been built at a time when Americans and their vehicles were lean. But the bridge was so long that it took me several minutes to walk it, wending my way around the shrubbery. At each end I came to high-ground forest. I could just make out where a road had once been. Studying my maps, I guessed that the road had been the original SR 76 coming from Adel, a highway that now crosses the Little a couple of miles downstream.

Though hidden in jungle-like swamp, this was a beautiful bridge. I felt like I had discovered the Deep South’s version of a Mayan temple. And I thought how much more inspiring this bridge was to look at than the stout, unimaginative, utilitarian “tee” constructions that are going up everywhere across rivers in the nation now, as the older bridges are replaced—new bridges that look like they have been copied from some soulless engineering plan in Soviet Russia.

The multi-arched bridge was not only attractive architecturally, it spanned a blackwater swamp sparkling in the sun. The forest, the glittering river, and the bridge all rubbed against and enhanced the beauty of each other. I looked for the proud metal plaque always found on such standout bridges giving the date of construction and sometimes even the name of the builder. But though I saw where it had been set in the railing, the plaque was gone.

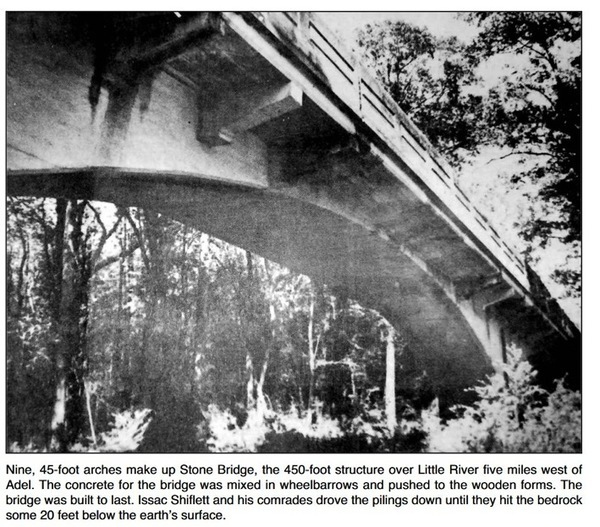

After the trip, I went to the national “Bridgehunter” site online. Bridgehunter’s goal is to provide an exhaustive “database of historic and notable bridges in the United States,” and to that end it tries to list every “crossing” on the Little River. It even lists those, I discovered as I paddled along, that had no more left to them than a couple of rotting wooden poles. To my surprise, this gorgeously arched bridge was not there! I wrote the site’s webmaster, James Baughn, to tell him about it, and he immediately replied, saying he’d look into the matter. Then in subsequent correspondence he told me what he’d found: the bridge is 450′ long, has nine arches total, and is of a “Luten Design,” known for “a type of concrete arch which was very graceful.” It had been built in 1925. He went on: “Luten bridges are increasingly rare, so this is a very historically significant bridge.” He said he’d made a page for it on the website.

Explore an out-of-the-way river, find an historic ruin.

Baughn also sent me an old newspaper clipping about the bridge—called “Stone Bridge”—a copy of which you’ll see among the other photos accompanying this report. Incredible to think, the newspaper states that the concrete for it was mixed in wheelbarrows and pushed to the forms. Considering how much concrete the bridge required, it had to add up to many tens of thousands of wheelbarrows full. For those of you who have worked with concrete, you’ll know that made for heavy labor indeed.

Stone Bridge, Adel News Tribune, 1 Oct 2014, Page 9-A.Just before the confluence of the Little and the Withlacoochee, at the Troupeville Landing, I met Phil and Cathy Hubbard, the first people I’d talked to since launching. Phil and Cathy are members of the southern Georgia watershed coalition WWALS (Withlacoochee, Willacoochee, Alapaha, Little, Suwannee). Having been alerted by the coalition’s president, John Quarterman, that I was coming downstream, they wanted to film a short interview for the group’s website. I had told them the probable time of my arrival. (If you want to see the interview, here ‘tis:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xGgZC5x8g80)

Photo: Kathy Hubbard of Phil Hubbard and Burt Kornegay at Troupville Landing.Besides meeting the Hubbards, I also picked up a mid-trip water cache at the landing. I’d hidden it there in a hollow live oak.

I’ll say no more about the wonderfully big Little River except this: It’s waiting for you to explore.

Onward to the Withlacoochee. A paddling map of the Withlacoochee that was published in the 1990s and that I’ve held on to for years calls it “Florida’s Most Exciting River.” That’s because it has whitewater shoals in a state where almost all the rivers are flat. And on its lower end, where the Withlacoochee crosses into Florida, there are also beautiful springs—Blue Spring and Suwanacoocheee being two. Their clear water boils up out of limestone sinks and flows boldly into the river’s blackwater.

Burt confirmed later he did see McIntyre Spring and Arnold Springs; he just couldn’t include everything in a brief report.

The only reference I can find to “Florida’s Most Exciting River” is in Canoeing & Kayaking Georgia, By Suzanne Welander, Bob Sehlinger, Menasha Ridge Press, Jul 14, 2015:

The local watershed alliance proposes the creation of a new canoe trail on the river, which was once billed as “Georgia’s and Florida’s Most Exciting River” in a vintage canoe guide.

There was an even older Canoeing Guide to the Withlacoochee River produced about 1979 by the late James H. Rainwater when he was at the regional Commission, before he became mayor of Valdosta.

The “local watershed alliance” the book refers to is of course WWALS Watershed Coalition (WWALS), and we have indeed produced a Withlacoochee and Little River Water Trail with online map, description, etc., and a printable pamphlet, plus soon a fancier brochure.

Of course, nobody said the Withlacoochee was like the Colorado; it’s unusual for this area because (like the Alapaha), it does have some rapids, at least when the water is low.

Back to Burt’s story:

In spite of its reputation for providing excitement, however, I did not find that canoeing on the Withlacoochee quickened my pulse, and I missed the Little’s fast-water swamps. The Withlacoochee turned out to be mostly straight, with a slow current. I came to no shoals that were more than Class I. They were short; and they were miles apart.

Even so, the “With,” as I’ve heard it called locally, was a beautiful river in its own right, and it was quiet too. I particularly liked seeing the knees and roots of its cypress and tupelos: they rose and wrapped themselves together into fantastic shapes.

One such amazing growth, human-sized, looked like a Grecian goddess rising out of the river. I fancied it could have been substituted for one of the Three Graces in the famous marble statue at the NYC Metropolitan Museum of Art. (See what you think in the photos below.) Of the three, I thought the root goddess most resembled the middle Grace in the statue, Aglaia, “Beauty.” But maybe I’d been alone on the river for too long.

Here’s the thing that most quickened my pulse: the Withlacoochee people I met. The first one, two day’s travel down from the confluence, was a man sitting on a little stool on the riverbank. It was near another abandoned (and handsome) span called “Spook Bridge,” held up by one huge arch. The man was round faced and unshaven, downright slovenly looking, in fact, and he sat next to a camouflage dome tent. In his left hand he held a fishing rod, in his right a half-gallon bottle of R&R Canadian Whiskey. “It’s a fine day!” he shouted when he saw me, “And last night I slept good!” He held up the bottle and sloshed it for emphasis. I saw it was 3/4s empty. “Caught me a fish too and I’m gonna eat it and sleep good again tonight!”

Wondering if he was going to chow down on the fish raw, scales and all, I wished him a very deep sleep indeed and kept paddling. A few seconds later, he let go with 4 good-natured gunshots. Glancing back, I saw that his target appeared to be a red and white Coleman cooler washed up on the far shore. At least, that was the general direction he was trying to point the gun. I started paddling again, then had this spooky vision of a stray bullet ripping through my back, the impact causing me to lurch forward, my heart pumping out my blood, filling the canoe with it, as the boat continued to glide placidly on down the river.

The next day I came to the first boat I’d seen on the Withlacoochee. It had a motor mounted in back, but it wasn’t going anywhere. Instead, it was floating from a line in the middle of the river, and it was empty. I coasted up, thinking the boat may have drifted downstream and the line had gotten snagged on the riverbed. Talk about finding river booty! Then I heard sounds behind me and, looking around, saw big bubbles breaking the inky surface. My first thought was, a gas leak of some type? I drifted down to look. Then I realized that the bubbles were coming up with breathing regularity, and suddenly all was clear: the boat belonged to a scuba diver, and he was right below me!

I paddled over next to shore and sat back in my boat, and about 10 minutes later the diver surfaced, wearing a wet suit. He spotted me and dove again, and I watched the bubbles come my way. Re-surfacing at my bow this time, he pulled back his mask, and I saw a man in his late-50s, with a friendly face. He said he was from the area, Florida born, name was Britt McClung, and for the fun of it he liked to search the bottoms of the nearby rivers. Over the years he’d found mastodon teeth, giant shark teeth, a saber-tooth cat’s “saber,” teeth of a dire wolf, and other fossils. He also found geodes—agatized coral—and that’s what he was looking for that day.

Britt said at one time he made his living by salvage diving for giant old-growth longleaf pine trees that, during the logging boom a century ago, sank in the river, where they had been preserved by its slightly acidic (i.e. bacteria-killing) blackwater. He’d dive, hook a cable to the logs, some of them 40′ long, winch them out of the river, and sell them. Virgin wood like that brings a good price.

Britt’s list of the fossil teeth he’d found made me think about present-day teeth in the river. I’d been seeing alligators and asked him if he could spot one coming towards him when he was down there. He said, no, he had a good diver’s light, but the water was so black he could see only about 2′ on any side. And he was very aware of gators. Before he dove, he explained, he’d sit still in the boat for around 15 minutes and watch to see if any of the reptiles cruised up to check him out. If one did, he’d dive somewhere else. I decided that I liked exploring the Withlacoochee just fine, in my boat.

We talked for quite a while, me in the canoe, him in the water. Then, needing to find a campsite for my last night, I paddled on down the river and he dove back under it. Late in the day, in camp, I saw Britt boating my way. He pulled in and gave me a burgundy geode he’d found. (I brought it home for Becky, who loves river booty.) He also showed me a fossil nautilus egg he’d uncovered. It was about the size of a goose egg. He said that when he finds one of these, he saws it open with a special blade at home, and every once in a while he’ll find a fossil embryo inside.

My last exciting encounter with humans happened because I broke a cardinal rule in camping. The rule is this: no matter how inviting a site is, don’t camp there if it can be driven to. When I see a prospective campsite, the first thing I do on landing is to scout out what’s behind it. If I find tire tracks, I paddle on. But when I find the campsite backed by impenetrable swamp or unbroken forest or a cliff, I know I’ve found a keeper.

The sandbar I wanted to camp on was backed by a bluff around 25′ high; but there was a trail leading down from the top. Walking up, I was disheartened to see a rough dirt road coming out of the woods to the bluff. But it was late in the day, campsites on the Withlacoochee had been infrequent, and this one was beautiful. The night was going to be clear. All I had to do was roll out my sleeping bag under the stars. I decided to break my rule and camp. Hey, no one would drive way out here on a Tuesday night, I told myself.

And no one did. It wasn’t until 12:30 a.m. Wednesday that I was startled awake by two trucks of teens who drove up to the bluff whooping and hollering, truck radios blaring. They were planning to party on my sandbar. I cursed myself for breaking my cardinal rule. Lucky for me, the teen in the first truck did not stop when the dirt track did. To judge by what I overheard (they weren’t conversing in quiet voices), he ran into something, knocked a headlight loose, got stuck. So, rather than troop down to party, the group spent an hour on the bluff trying to get the truck unstuck.

“Look at my fucking headlight!”

“Gimme me a beer, dude!”

“You got a winch on your truck?”

Then I heard one of the girls say, “I got to pee!” And down the trail she came with a flashlight, followed by another girl. The sandbar was lit up by a moon that was almost full, and soon there were two more moons shining. It was as if the missing Graces, Euphrosyne and Thalia, had appeared. And then (I’m not making this up) high in the sky, as if it were spilling out of the Big Dipper, Ursa Major to the ancients, I saw a beautiful star descend, as big and bright as Venus. I say descend because this was no “shooting” star. Instead, it seemed to float down towards the earth as if suspended from wings, glowing brightly all the way. I took it for a heavenly sign, but I haven’t deciphered it yet.

Blinded by each other’s flashlights, the girls didn’t see the spectacular falling star or me either, lying there in my sleeping bag. “Ouch, a thorn stuck my butt!” one laughed. I breathed a sigh of relief when they followed their flashlight beams back up the trail. I breathed an even deeper sigh of relief a few minutes later when I heard truck doors slam shut and the group drive off to party somewhere else.

I’ll close by saying that although most canoe trips end when you take off the river, this one did not. It didn’t end until the night I got back home and the phone rang: it was Colbert! Colbert Sturgeon, to be exact. He called to say he was pleased that I had stopped by his Little River home and left him a note.

Colbert told me he had worked as an insurance and investment salesman, American Express, I think it was, drew a big salary. He was married, had 2 daughters and all the stuff that’s supposed to make life happy. But when the daughters were grown, he divorced his wife, and with a lot of looking at remote places, found 50 acres for sale in the middle of nowhere on the Little River, bought them in 1990, moved there 1995. He’d done all the building by himself. Colbert emerges from his swamp fastness occasionally to teach primitive skills in wilderness workshops. He said he’d been featured in a National Geographic TV show, “Live Free or Die.”

Turned out Colbert also knew several of the same stone-age practitioners whom I got to know and like back in the 1990s when Becky and Henry and I took part regularly in primitive-skill rendezvous in the South.

I told Colbert I’d let him know the next time I paddled down the Little. He gave me his post office box #, in Valdosta. He goes to the town from time to time, where he picks up mail, stocks up on food, make calls. To get there, he boats down the river a few miles to a friend’s landing, where he has a truck parked up on the bluff.

When Colbert Sturgeon goes to town again, he’ll find a copy of this trip report in his mailbox.

Burt Kornegay

Indeed Colbert Sturgeon goes to town. He came to Azalea Festival among 20,000 people and had a long chat with Gretchen at the WWALS booth. Here’s more about him, in Live free or die: Life according to Colbert, by Tiffany Wilson, in Rethink:Rural, December 2, 2015. That article pictures Colbert Sturgeon, his swing bridge, and his house.

Colbert Sturgeon is actually in an three-season series by National Geographic, Live Free or Die.

Come on down to Troupville Boat Ramp for a cleanup, Saturday morning, April 21, 2018, mostly down at the confluence on the site of old Troupville.

See the WWALS calendar and the WWALS outings and events for more things coming up. Trips like Burt are not in there, but we’ve also had paddlers from afar all the way down the Withlacoochee and the Alapaha Rivers recently; more on those in upcoming posts.

-jsq, John S. Quarterman, Suwannee RIVERKEEPER®

You can join this fun and work by becoming a WWALS member today!

Short Link: